To continue from my previous post (How to Search for Wills and Probate in England)…

Once you have received the will you ordered you will be eager to get on and read it and see if it contains information about other ancestors, or whether it gives you the link between families that you are looking for. But don’t rush at this. There is an art to reading wills and inventories, and quite often, especially if the will was written before 1800, you will need to learn some paleography skills too.

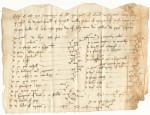

If you are lucky, a will sometimes has an inventory attached, which is basically a list of assets and possessions and what they are worth, added up to give the total estate’s worth. These can be really fascinating, giving you a real insight into an ancestor’s lifestyle and giving you a solid picture of the furniture, clothing and general bits and pieces that make up a person’s life. They can include such items as beds, chairs, furnishings, foodstuffs, livestock and crops – and you will also get an idea of the type of property they lived in as each room is itemised for its contents.

The Will

Onto the will itself – if it’s easy to read, then all you need is a basic understanding of the way wills have been generally formatted so you can differentiate between the clerk’s standardised text and your ancestor’s “voice”.

As in most legal documents, don’t expect there to be much punctuation!

The Preamble

A very usual beginning will be: In the name of God Amen following by the testator’s name, parish and occupation. Very often this will be followed by a statement explaining that although sick of body is of full and perfect memory to prove that he knew what he was doing (i.e. he was mentally able to write a valid will). This will usually be followed by some standard text committing his body to Almighty God and his body to burial in the parish churchyard etc. If the testator was Catholic, or of a very profound religious turn of mind (or perhaps hedging his bets), there may be a lengthy religious preamble where the testator expresses penitence, or asks for forgiveness etc. Whilst a lengthy preamble like this can suggest strong religious beliefs on behalf of the testator, one should not rule out an enthusiastic clerk using conventional formula!

Payment of debts and funeral expenses will be the next thing to follow, along with the wish to annul any previous will.

The Bequests

Now you are into the juicy part of the will, where the testator shares out his property, monies and/or possessions to his family and friends. Each bequest usually begins with the word “Item” followed by I leave to or I bequeath to then the name of the beneficiary. To be sure that the bequest goes to the right person, wills usually describe the legatees very well, giving the relationship to the testator, where they live and (for a married woman) the name of their spouse.

If there are any child beneficiaries, their legacies are very often held in trust until they reach the age of 21. This can help you to confirm approximate ages for children or grandchildren.

Sometimes, property & monies that are to be held in trust, shared out, or paid at intervals, would be wrapped up in extremely lengthy and complicated legal jargon covering every last detail and eventuality (such as the legatee dying before receiving their share). This can make for rather tedious reading (especially as there is very little punctuation!), and while it is worth going through it to make sure there are no significant details about the family that you need to know, don’t worry if you don’t understand everything. It is just worth knowing that your ancestor was keen to make sure every T was crossed and every I dotted!

Sometimes, the character, beliefs or attitudes of your ancestor will break through all the formal language giving you a glimpse of the real human being. I recently transcribed a will for a client whose ancestor insisted that if his wife should marry again, then his son should “slam the door in her face”. This kind of emotive language can raise a few questions about the relationships between husband and wife, father and son etc, and is delightfully intriguing! (By the way, I did check, but as far as I could find out, the wife never did marry again…)

The Executor

All wills name an executor (or female executrix) – sometimes two – who were appointed to supervise the administration of the will. These were very often trusted close friends or relations (mostly the wife or eldest son).

The End Bits

The last few words of a will are often something like: In Witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and seal this 15th day of July in the year One thousand seven hundred and eighty-two

The testator will then sign, and the witness statement will be underneath as follows: Signed sealed published and declared by the said [testator’s name] as for his last Will & Testament in the presence of followed by the signatures of the witnesses.

Probate

Either on the bottom, the back, or on an attached piece of paper, the probate will state the date that probate was granted along with the names of the executors. The amount of the estate is sometimes stated.

Paleography

If the will was written before 1800, and particularly if it is a 16th or 17th century will, you might find it extremely difficult to read, and can sometimes look as though it’s written in a different language. The earliest wills were written in Latin, and in this case you will need to find a Latin transcriber.

However, if it is English, the clerk’s hand can be very difficult to decipher, as well as the fact that many words were spelled completely differently, some are out of use completely, and many letters look almost unrecogniseable to the way we would write them today.

If the will you have ordered is like this – don’t panic! Paleography (or palaeography if you want to be absolutely correct) is not a difficult skill to learn, and the more you practise reading old handwriting, the easier you will find it. The National Archives have an excellent online tutorial in reading handwriting from 1500 to 1800 and you can start this tutorial here.

If you don’t have the time to do this yourself (and even when you’ve learned a bit of paleography, it can still be a lengthy process if the will is a long one), most professional genealogists will transcribe a will for you for a fee.

Nuncupative wills

If a person’s final illness was very short and they did not have time to make a will, often an oral statement (often known as “deathbed wills”) would be made and accepted by the church courts. These wills were only valid up until 1837 (with the exception of those in the armed forces who died in action).

Administrations

Administrations (often abbreviated to “admons” in record office indexes) can often be found where a person died intestate (without leaving a will). They are letters of administration granted by the court to those it considered legitimate administrators – usually the widow, or eldest son.

A few more notes to remember. Don’t be too worried if you have the will of an ancestor, but he does not mention all his children, or only leaves a small sum of money to them. This does not necessarily mean that they have been “cut out” of the will. It may be that they have already been provided for, and if they are only left a small amount, the testator may have wanted to mention them to confirm them as their son, but in the knowledge that they had no need for any great legacy.

Also, remember that the word “cousin” can refer to a wide range of kin, and that other relations, such as father, brother, son etc can also refer to in-laws.

This has been a very brief guide to wills, but if you would like to learn more, I have a course at Udemy which will take you through the whole process of searching for, ordering and reading wills. Have a look HERE.

(Picture supplied by Staffordshire Record Office)