I often get asked by clients if I can help them find a missing father where the child is illegitimate, and to be honest, my heart tends to sink a little at this request. Most of the time, it’s almost, if not completely, impossible to find a missing father using the usual genealogical sources. However, these days, there is more hope for finding the father of an illegitimate child due to DNA testing.

But first – let’s look at how you know, to start with, that a child is illegitimate.

After 1837, the first hint you might have that a person was illegitimate is if the father’s name is missing on the marriage certificate. But, even when a person didn’t know their father, there might still be a name here – which can confuse the issue. The stigma of illegitimacy was such a shameful thing that many people would invent a father, just so they could look socially respectable. This, of course, causes much confusion to future genealogists.

The next hint comes when you look at a birth certificate or a baptism, and find that no father’s name is given. So, if there was a father’s name on the marriage certificate, but no father at birth – then either the name on the marriage certificate was a stepfather – perhaps the person their mother married later – or it was made up, as I said previously.

In illegitimate cases, the surname of the child is usually the same as the surname of the mother – and in a birth certificate you might also have a look at the address of where he or she was born. Sometimes you can trace this back to a home for single mothers or something similar.

In baptisms, very often the child will be described as a bastard, base born – or in a slightly more genteel way of putting it – the ‘natural’ child of the mother.

Very occasionally, you might be lucky, and the father may be mentioned in the baptism. This actually happened in my own family tree, which enabled me to trace my male line back under a different surname. But this is fairly rare – and I count myself extremely lucky in this case. But if you only have a birth certificate, then in this case – ALWAYs look for the baptism as well, just in case the father is named. And vice versa – it’s always possible that the father was not named at the baptism, but may be in the birth certificate – as long as it’s after 1837 of course.

But mostly, this is going to be a disappointing result. So, what’s your next step. Well, this depends on what dates we are looking at.

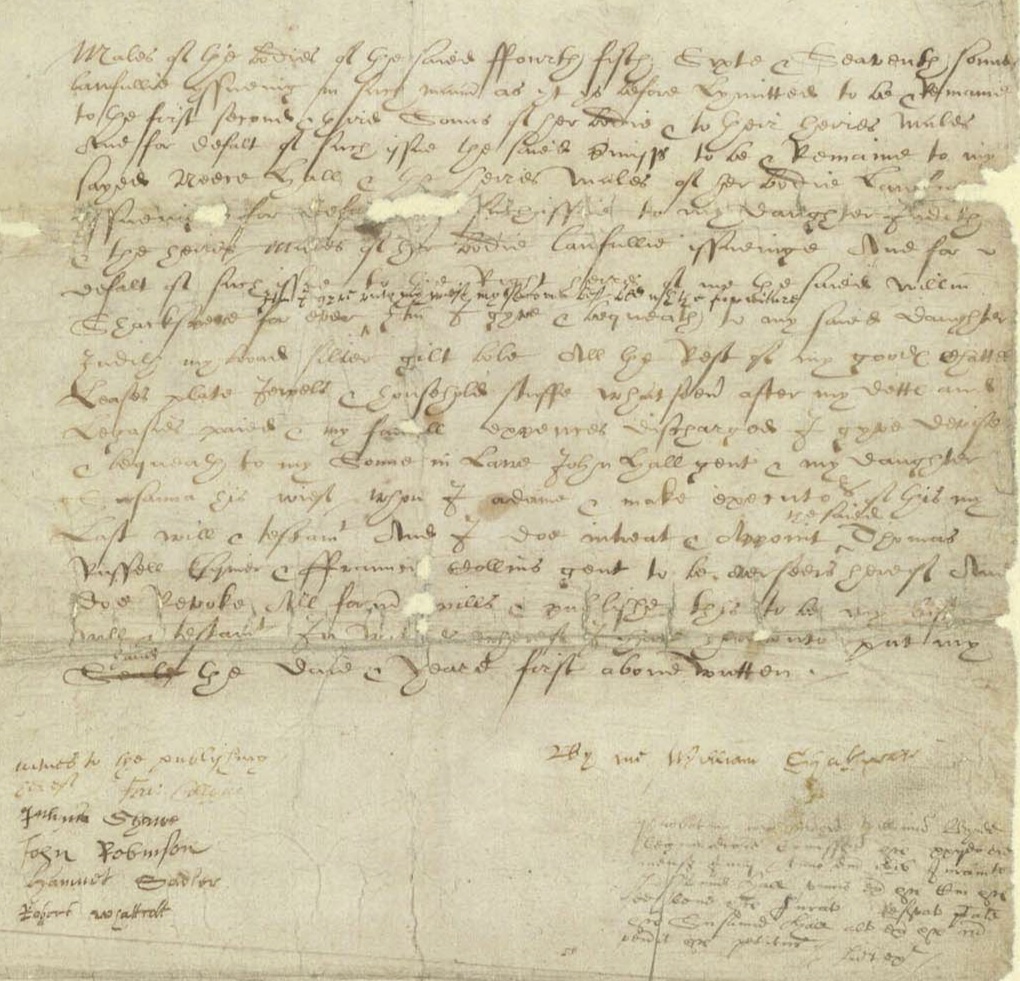

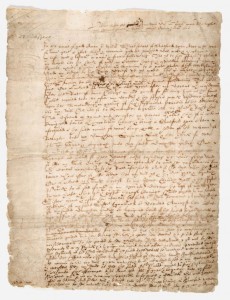

From the 16th to the 19th century – sometimes a woman would apply to the local Parish Overseers for a Bastardy Order, which would then put pressure on the named father to provide financial support to the mother and child. The best place to find these are in local record offices – and you can search these by carrying out a search on the Discovery page of the National Archives website.

But – don’t be too disappointed if you don’t find one. These are also fairly rare, considering the stigma of illegitimacy, and the circumstances of the pregnancy. There may be circumstances in which the mother did not know the name of the father herself – though this would be more likely the case in a large city or town.

Another thing you can try if we’re in the 19th or early 20th century is to look at the closest census record to the birth. Where was the mother living? Was she working as a servant? Does the child have a distinctive middle name which matches someone else in the household? This is a bit of a long shot – and is obviously something that cannot be proved – but you might come up with a possibility – and then if the suspected father was wealthy, you could try searching for a will to see if the illegitimate child is mentioned.

If the illegitimacy is within the last few generations, and you’ve tried everything mentioned above, then your next step is to try DNA testing. Once you have registered your results then you will be notified of any matches – and those matches that don’t fit with the rest of your family tree may well be the family of that missing father – so you can then carry out research on the matching family tree (with the permission of the person with the matching DNA of course).

This is not quite as easy as it sounds. I’ve had quite a few clients requesting research in this manner and it is still quite hit and miss. If you have a 2nd cousin match, then you share a great grandparent – which means researching the descendants of the great grandparents of the match to try and find any likely persons who were in the vicinity of the mother at the time of the birth. Sometimes, there are just too many results, and you can only come up with possibilities. However, sometimes you might come up with someone who fits the bill perfectly – and I have had the occasional success in this area.

So – finding a missing father is not easy – but sometimes it can be done – and sometimes it can’t. Most of us will have at least one somewhere – and sometimes, we just have to live with the disappointment, and move on to another line in our family tree.

So – good luck with your research – and do let me know if you’ve had any success in this area and how you did it. Please don’t forget to subscribe if you want more advice and tips in family history research in the UK