This article (by me!) was first published in Family History Monthly in December 2007 under the title ‘..And a Partridge in a Pear Tree.’ I thought it would make a nice blog post for the season. Hope you enjoy.

Today, Christmas is effectively over after Boxing Day, and apart from the New Year celebrations, many of us are back at work on the 27th, all festivities behind us. For our society, and its worship of the great God Commerce, Christmas starts soon after Halloween, builds up into a crescendo of hysterical money-spending, and culminates in an orgiastic climax of partying, drinking and over-eating.

The Yuletide festival was very different for our distant ancestors. Christmas began at midnight on Christmas morning, and lasted until Twelfth Night – the night beginning on January 5th (with Twelfth Day being January 6th). The only tradition to have survived that relates to these twelve days is keeping our decorations up until January 6th, when with relief we pull down the drooping tinsel, and sweep away the thick pile of Christmas Tree needles.

Very few of us, I am sure, know why we do this, and neither do we know much about the Twelve Days apart from that rather strange and slightly irritating carol.

In order to understand the Twelve Days, we have to go back even further to the centuries following Christ’s lifetime when the Christian church was attempting to establish a nativity festival and the dates of related events. The idea of celebrating Christ’s birth was not a popular one until the end of the first century – but nobody knew on what day he had been born, and it was not until the year 336 that December 25th was chosen. This was partly because of a belief that the Annunciation – and Christ’s conception – was on March 25th, and therefore his birth must have taken place nine months later. But it was also related to a pagan festival that was already in place involving sun worship – and the Christian ‘Sun of Righteousness’ intermingled with the belief in a Sun God. The date of the sun’s rebirth, according to this belief, was 25th December.

This date was at that time the date of the winter solstice, the day when the sun was ‘reborn’ in the sky and conquered the dark months of winter. This was a major feast day in the Roman Empire and a culmination of the Feast of Saturnalia (December 17th to 23rd) when social order was overturned, and servants could make the rules. Holly – a symbol of the god Saturn – was used for decoration, and the festival also included the making and giving of small presents. These traditions were incorporated into the later Christian festival.

The next decision to be made was the hour of Christ’s birth, and this was established as midnight on the morning of the 25th, when a mass was to be held, hence: Christ’s Mass, which became Christmas.

The other name for this period, Yuletide, stems from the old pagan festival of fire and light, known as Yule in England and Scandinavia. The druids used to light a Yule log which was kept burning for the twelve days of the winter solstice. This tradition was still being practised in medieval times and the log would be carried into the house on Christmas Eve, decorated with greenery and ribbons, lit with the end of last year’s log and kept burning until January 5th. There are still remnants of this tradition today.

In the pagan festival, the twelve nights following the winter solstice represented the twelve signs of the zodiac. There was also an Egyptian festival celebrating the birth of the gods on January 6th. However, in the 4th century, January 6th gained popularity as the date that the three wise men came to see the infant Jesus, and so became the Feast of the Epiphany. The French church proclaimed the period between the two dates to be sacred, and so began the celebration of the Twelve Days of Christmas. Several Christian feast days became incorporated into this period, including St Stephen’s Day on the 26th, the Feast of St John the Apostle on the 27th and the Feast of the Holy Innocents on December 28th. Whether by design or not, by entwining Christian festivals with pagan ones, the Church successfully increased the popularity of its own celebrations.

By the Middle Ages, thismix of the pagan and the Christian had become well established and was preceded by a period of four weeks of fasting known as Advent. Ironically, today’s advent calendars bear little relation to this, with doors opening to reveal chocolates or sweets. The fasting on Christmas Eve was particularly strict, and no meat, eggs or cheese were eaten on this day.

By the Middle Ages, thismix of the pagan and the Christian had become well established and was preceded by a period of four weeks of fasting known as Advent. Ironically, today’s advent calendars bear little relation to this, with doors opening to reveal chocolates or sweets. The fasting on Christmas Eve was particularly strict, and no meat, eggs or cheese were eaten on this day.

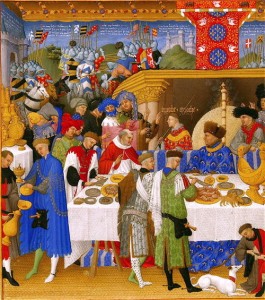

Indigestion was no doubt as much a part of Christmas then as it is now, as banqueting – for the rich at least – started on Christmas Day and was repeated on some of the following days up until Twelfth Night. After four weeks of fasting, this must have come as a shock to the system. Goose, swan or venison might be eaten, and in 1289 the Bishop of Hereford was reported to have presented a Boar’s Head to his guests, which became standard fayre for the elite.

For most people, Christmas Day would start with attendance at Christmas Mass at dawn. The congregation would hold lighted tapers while Christ’s genealogy was sung. Afterwards, they would go home and begin their first big meal of the season. In some areas, depending on whether your local nobility was of a generous leaning or not, the rich were expected to keep an open house for the locals. The food might have included a precursor of today’s mince pie which was made with real meat, fruit and spices. Christmas pudding was originally a dish of porridge, currants and dried fruit eaten on Christmas Eve after the day’s fast. As far as I can gather, there was no tradition of gift-giving on the day itself – and certainly no Father Christmas or Christmas tree, neither of which became a part of Christmas until the 19th century. The day was all about food and community, whereas today we focus more on family gatherings.

Over time, entertainments became part of the merry-making, and by the early 15th century landowners were employing theatrical troupes and musicians, and mummers’ plays and dances were performed in some villages. By Tudor times, amusements might also include jesters and acrobats. Some parishioners would pool together to hire their own players – or even put on their own plays in the village church.

On 26th December, the church distributed the money from the alms boxes to the poor of the parish, which is why we call this Boxing Day. Today’s tradition (though probably fading out) of giving small gifts to delivery workers stems from this practice.

The Feast of the Holy Innocents on the 28th was a day for commemorating Herod’s cruelty when he ordered all children under the age of two to be slaughtered. It has been said that in medieval times children were beaten on this day to remind them of this. However, there is also evidence that may suggest a pre-Christian ritualistic scourging which is not necessarily confined to Christmas or to children. The beautiful Coventry Carol, which originated with the Coventry Corpus Christi Mystery Plays in the 15th century, suggests a more sensitive approach, particularly in its chorus and last verse:

Lully, Lullay, thou little tiny child.

Bye, bye, lully, lullay.

Lullay thou little tiny child

Bye, bye, lully, lullay

Then woe is me, poor child, for thee,

And ever mourn and say;

For thy parting neither say nor sing,

Bye, bye lully, lullay.

Whatever the tradition of Holy Innocents Day, it was certainly thought to be unlucky, and most people would not think of beginning anything on that day, as it would be unlikely to ever be completed.

As for New Year’s Day, we know, of course, that January 1st did not officially become the start of the New Year until 1751. However, surprising though it may seem, New Year celebrations did take place on this day, following an old Roman tradition. It is on this day that we find evidence of the giving and receiving of gifts amongst the upper classes and from master to servant – and there is no reason to believe that the exchange of gifts did not happen in the lower classes as well. It is this tradition that is believed to be the forerunner of the modern day Christmas present.

It was at New Year that the ‘wassail’ would be heard. The word comes from the Saxon waes hael and means ‘be well’. In Saxon times the lord of the manor would shout ‘waes hael!’ to his household, and they would reply: ‘drink hael!’ (drink well and be healthy). By the Middle Ages it had become a tradition to toast each other in this way – usually with a form of mulled ale, cider or wine. By 1600 many commoners had begun to take the wassail bowl from house to house, singing as they went, a practice that Shakespeare probably was involved in, and which has survived into the modern Christmas Carol singing from door to door. There was also a ceremony whereby apple trees would be sprinkled with the wassail to ensure a good harvest in the coming year.

Twelfth Night itself signalled the end of the Christmas holiday, but was itself a time of religious services and feast-making. It began with a dramatic church service and ended with what was probably the most lavish feast of the year (for the upper classes and royalty at least) and there were many entertainments and merry-making. Twelfth Night cake was an essential part of the festivities, and often contained a pea and a bean, whoever finding them becoming King and Queen for the night.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Twelfth Night period was a tradition that had developed from the Roman Saturnalia festival. In Roman times, the Lord of Misrule represented the god Saturn and one member of the community would be appointed to take on this role. This practice lasted well into the Middle Ages and the Tudor periods, particular in larger households, universities and law schools. A mock ruler would be chosen for the twelve days who would be in a position of authority and in charge of entertainments. The chosen one would then appoint his own guards and followers and they would dress themselves up in the most colourful garbs, cover themselves up with ribbons and lace and march to the church. A record of the written appointment of one Lord of Misrule for the household of the Right Worshipful Richard Evelyn is shown below:

‘Imprimis, I give free leave to Owen Flood, my trumpeter, gentleman, to be Lord of Misrule of all good orders during the twelve days. And also, I give free leave to the said Owen Flood to command all and every person or persons whatsoever, as well servants as others, to be at his command whensoever he shall sound his trumpet or music, and to do him good service, as though I were present myself, at their perils I give full power and authority to his lordship to break up all locks, bolts, bars, doors, and latches, and to fling up all doors out of hinges, to come at those who presume to disobey his lordship’s commands. God save the king!’

It is not difficult to imagine the riotous and often scandalous events that were no doubt caused and presided over by the Lord of Misrule. Their antics often caused church officials, particularly puritans, some serious concern and there were regular calls to ban the tradition. However, many abbeys and cathedrals had their own version from the 10th century, known as the Boy Bishop, who presided from the day before the Feast of the Holy Innocents until the end of the following day. As well as being in charge of services, he sometimes would lead a procession, collecting money from wealthy households and spectators which would be used for parish funds.

On 7th January all merry-making came to an end and in the countryside preparations would begin for ploughing the fields. In fact, the first Monday after Epiphany was known as Plough Monday.

So Christmas was very different for our ancestors – but not quite the strongly religious festival that we may imagine. The church had allowed many secular entertainments and pre-Christian traditions to become part of the nativity celebrations, and perhaps the feasting, drinking and general carousing was even more of a feature than it is today.

The following verse is taken from a long poem by George Wither written in the early 17th century.

Now all our neighbours’ chimneys smoke,

And Christmas blocks are burning;

Their ovens they with baked meat choke,

And all their spits are turning.

Without the door let sorrow lye;

And if for cold it hap to die,

We’ll bury’t in a Christmas-pie,

And evermore be merry.

Which rather sums up the light hearted aspects of Christmas – and perhaps reminds us that, despite the fact that it is predominantly a Christian festival, we like to enjoy a mid-winter festival that brightens up the dark days of winter, just like our pagan forebears did.

Wassail!

PS – Looking for a last minute gift idea? Have a look at my special genealogy gift vouchers that you can print or send by email: See THIS PAGE

It’s been a long time since I last posted, and this is because I have recently moved house – to the very rural village of Whatcote in Warwickshire. Of course, being interested in all things historical, I have looked on the internet for any history linked to this village – but all I have found is that the Church of St. Peter’s was partly destroyed by a rogue German bomber on its way to blitz Coventry during the war, and that Cromwell stayed here before the Battle of Edgehill. I would be very interested to learn more Warwickshire history specifically relating to this extremely beautiful area of countryside.

It’s been a long time since I last posted, and this is because I have recently moved house – to the very rural village of Whatcote in Warwickshire. Of course, being interested in all things historical, I have looked on the internet for any history linked to this village – but all I have found is that the Church of St. Peter’s was partly destroyed by a rogue German bomber on its way to blitz Coventry during the war, and that Cromwell stayed here before the Battle of Edgehill. I would be very interested to learn more Warwickshire history specifically relating to this extremely beautiful area of countryside.